A bond is just one way for a company to borrow money, you become its lender by investing in its bond, and yield is the annualized return to you from the coupon and principal payments relative to the amount you invested.

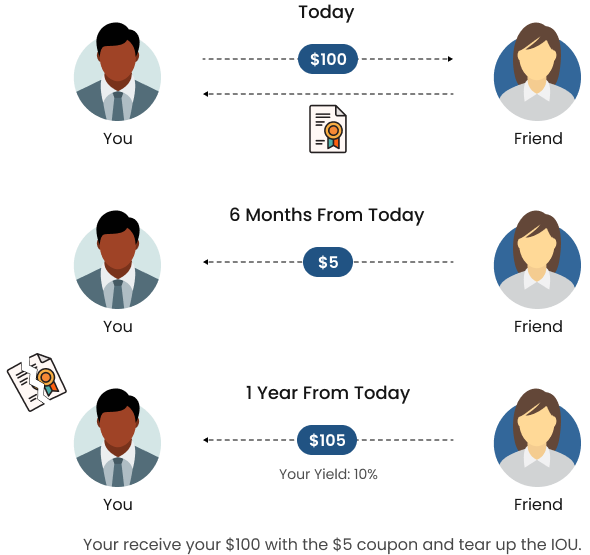

Suppose a friend would like to borrow $100 in return for one coupon payment of $5 in 6 months and another $5, along with your $100, in one year.

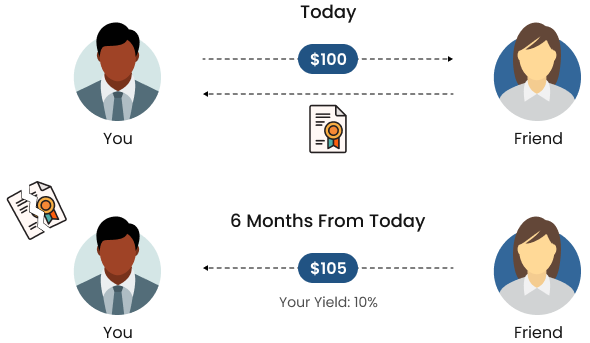

Alternatively, your friend would like the option to repay your $100 with the first coupon payment in 6 months. She may decide to repay you in one year and would like to let you know after she borrows the $100.

If you are repaid your $100 in 6 months with $5, your yield is still 10% on an annualized basis so you agree.

Now, your neighbor hears about your loan and likes the terms. Your neighbor will pay you $101 today to step in as lender on exactly the same terms.

Why?

A Make Whole of 5% means the redemption price would result in a yield of 5% on the obligation until maturity if it was sold, so your friend would pay $102.44 of principal along with the $5 coupon, and your neighbor’s yield would be 12.75%. A Make Whole requires the borrower to pay the entire difference between the obligation’s coupon and the Make Whole rate to the lender upfront. The economic effect is that the lender can reinvest the redemption proceeds at the Make Whole rate until maturity receive the total return of the original obligation.

In practice, Make Whole rates are generally 0.15% to 0.25% above the US Treasury yield to the obligation’s final maturity meaning the lender can invest essentially risk free and receive the economic benefit of owning the bond for the longest possible duration.

In Summary:

A Make Whole is a way to insulate investors from the negative effects of prepayment and for that reason, the economics of Make Whole calls are generally ignored.

For bonds which may be called by the issuer at a fixed price, the date that results in the lowest, or worst, possible yield at its corresponding price is the Workout Date. For analysis, and trading, of fixed price callable bonds, the yield referenced is generally the Yield to Worst and maturity comparisons are to the corresponding Workout Date. In the event a bond is not repaid on a Workout Date prior to maturity, the return on investment will be higher than the Yield to Worst, however investors should always refer to the final maturity to understand the latest possible date when the issuer is required to repay principal.