Credit risk is the main factor that distinguishes a corporate bond from a US Treasury- if it didn’t have any, it would be a government bond.

Types of Credit Risk:

- Fundamental

- Market Implied

Fundamental Credit Risk:

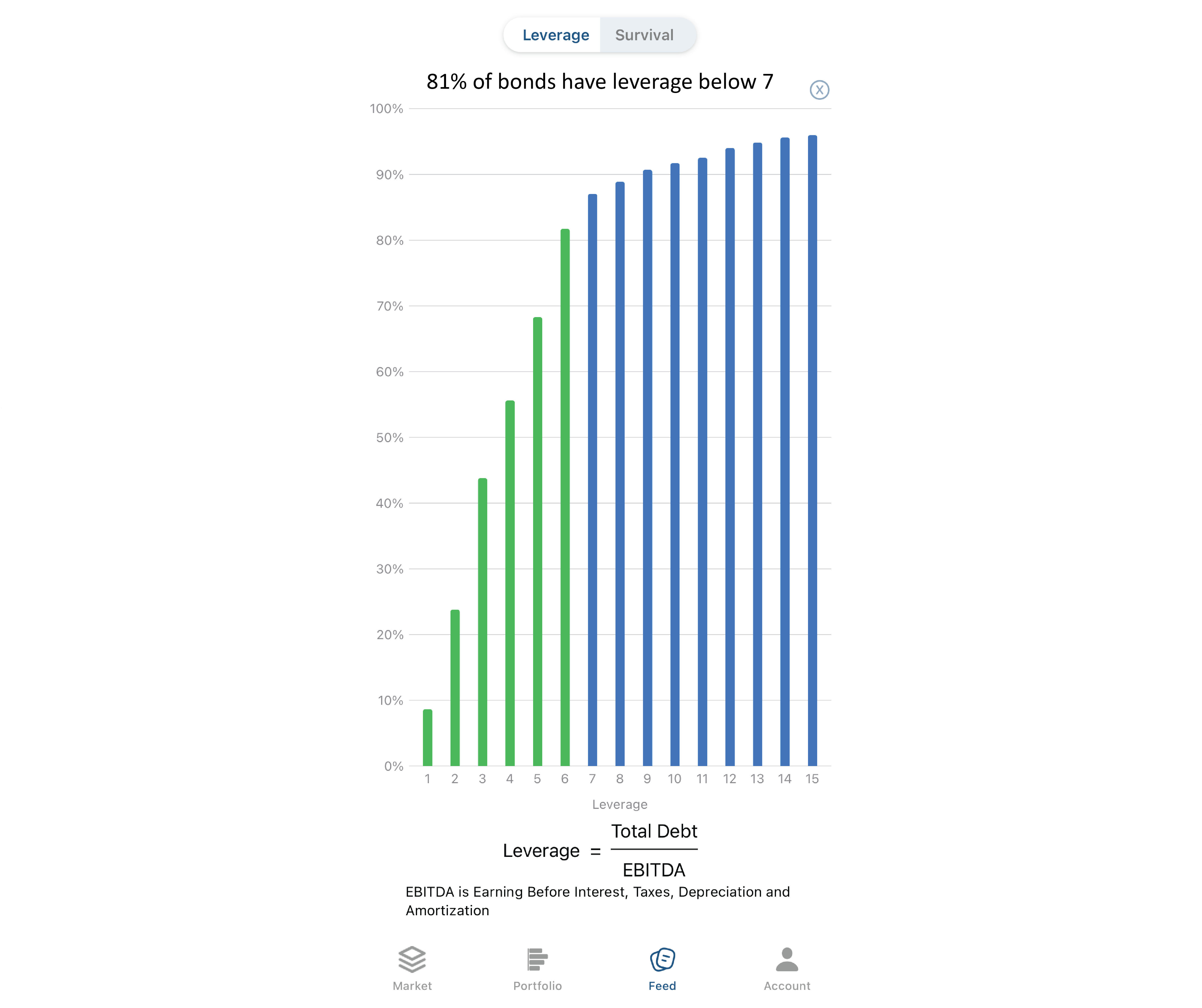

This is the risk that a corporate borrower, the bond issuer, won’t be able to meet its financial obligations. How much do they owe? What is their earnings power? For non-financial institutions, the most import metric is leverage which is the ratio of Total Debt to EBITDA, a broad definition of earnings.

EBITDA is Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization

EBITDA is Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization

The lower its leverage, the more the company is earning relative to its debt. Bank leverage figures are not traditionally included since they would be high although the wisdom of this convention is questionable in the wake of Silicon Valley Bank’s demise:

Other good fundamental credit metrics are:

Market Implied Credit Risk

Since corporate debt isn’t risk free, two facts can be stated about credit risk:

- When comparing two bonds of the same maturity, investors will demand a greater spread above the riskless government bond yield for the riskier issue.

- Each additional day until maturity adds incremental credit risk.

Every corporate bond yields some amount, or spread, above the government bond yield of the same maturity

Every corporate bond yields some amount, or spread, above the government bond yield of the same maturity

The difference, or spread, between the yield of a corporate bond and the interpolated government bond yield of the same maturity is the G-Spread. The G-Spread is the market’s assessment of credit risk in the corporate bond and an investor’s reward for taking that risk.

Survival Probability

The G-Spread, or credit spread, is a valuable indicator and one of the components used to calculate a corporate bond’s survival probability. The others are:

- Maturity

- Expected Recovery Rate. If the issuer isn’t able to repay its bond in full, any residual value reduces an investor’s loss.

Survival Probability Formula

Survival Probability Formula

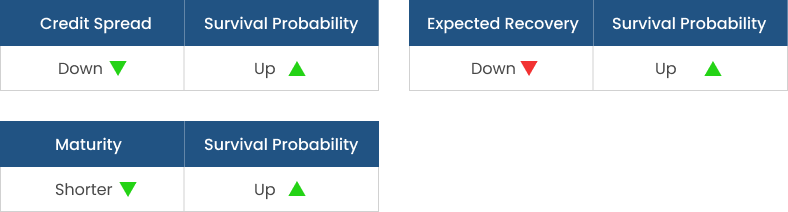

When the component levels change or different maturities are compared, the effect on the Survival Probability is as follows:

An increase in any component factor decreases the Survival Probability

An increase in any component factor decreases the Survival Probability

A decrease in any component factor increases the Survival Probability

A decrease in any component factor increases the Survival Probability

Credit spreads increase with credit risk and every extra day until maturity adds risk so the effect of these changes is intuitive. The reason an implied survival probability decreases with expected recovery, however, is less obvious but simple. If a bond is expected to recover 97% of its principal value following a default and is trading at a price 97, the market is saying it has effectively defaulted already. If, on the other hand, its recovery value is expected to be 10% and it’s trading at 97, the market is predicting that bond payments will continue for the foreseeable future.

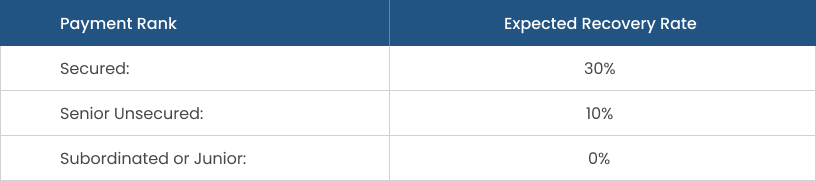

For performing credits, the market assumes a defined recovery rate for each payment rank which is the priority of a bondholder’s claim in a default. Secured is the highest rank, with specific assets pledged as collateral towards the amount owed. Senior Unsecured bondholders have no claim to any particular collateral but are first in line to the remaining assets not pledged to secured creditors. After the senior unsecured creditors come holders of Subordinated or Junior bonds. They have a claim, although only to what remains after the senior unsecured creditors are repaid. Given this hierarchy, for the purpose deriving survival probabilities, the following recovery rates are assumed:

As an issuer approaches default, bond prices of all maturities converge to the recovery level expected for their payment rank. When that happens, those recovery rates are used to derive the survival probability.

A variation on the survival probability is used by banks to calculate their risk-weighted assets using the same component factors of spread, maturity and expected recovery. Agency credit ratings are ignored.

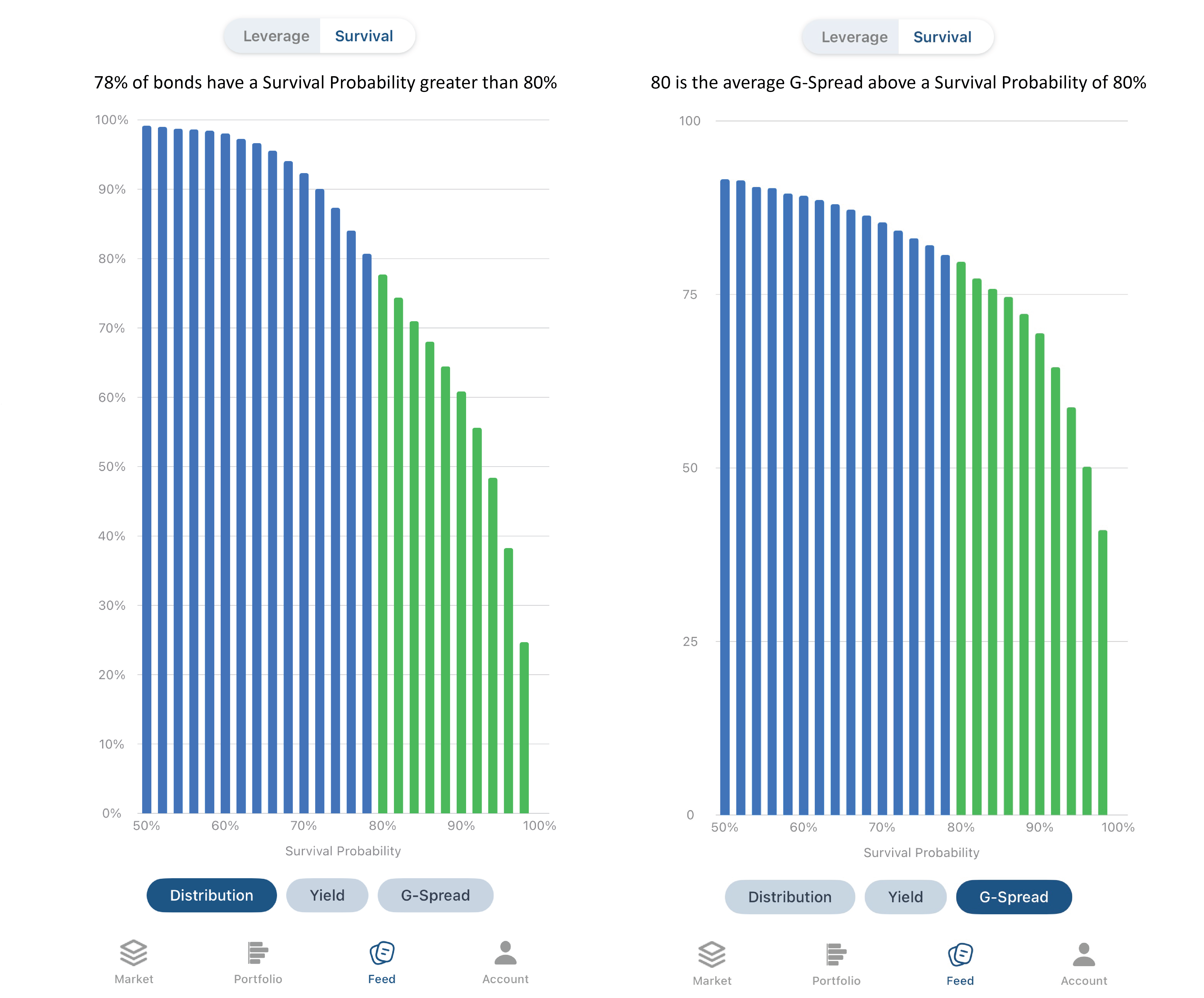

Below are the distribution of $4tn of corporate bonds and the average G-Spread above a survival probability of 80%.

Why Survival Probability?

Although a credit spread is an excellent indicator, when comparing two bonds from the same issuer with the same spread but different maturities, the risk that an investor is not repaid is greater in the longer bond. Survival probability incorporates the credit risk of a bond as indicated by the credit spread as well as the amount time until maturity.

Agency Credit Ratings

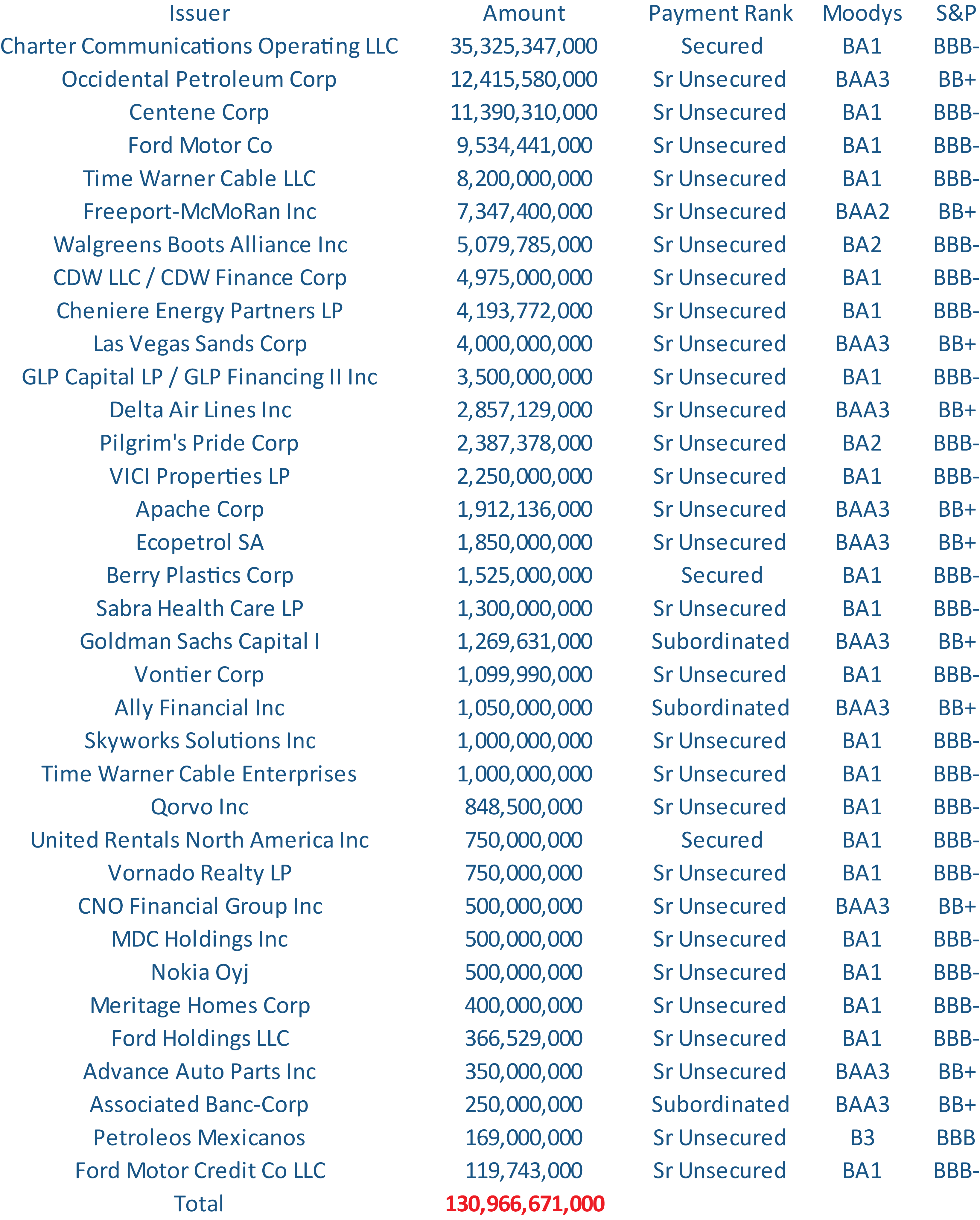

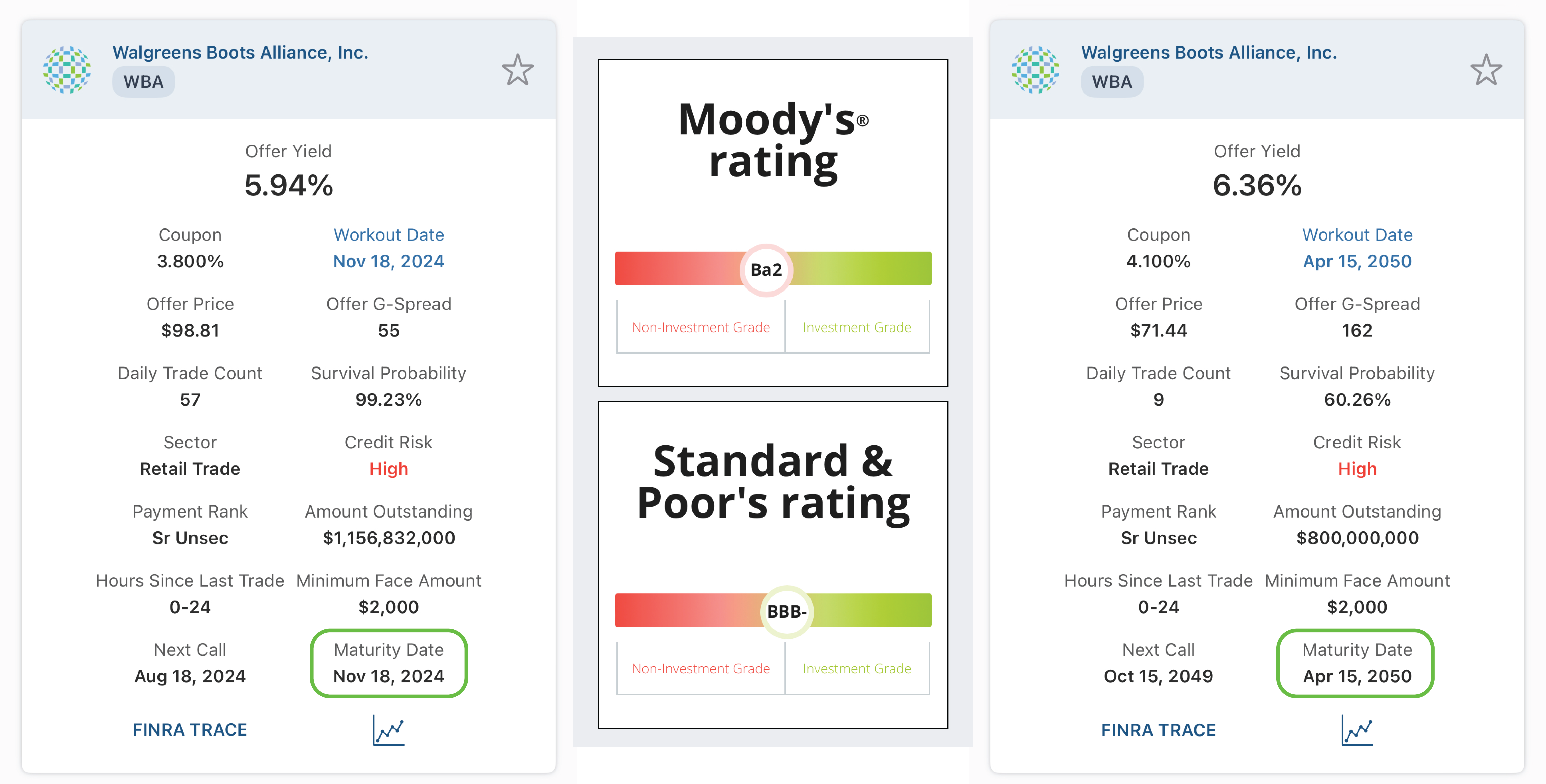

For individual investors, agency ratings should be taken with a grain of salt. While their most frequently quoted distinction is between investment grade and non-investment grade companies, they disagree regarding over $130bn of actively traded bonds as of April, 2024:

Issuers and payment ranks rated investment grade by one agency and non-investment grade by another.

Issuers and payment ranks rated investment grade by one agency and non-investment grade by another.

For bonds from the same issuer, rating agencies distinguish only by payment rank, not by maturity:

Each agency assigns their same respective credit rating to a senior unsecured Walgreens Boots bond maturing in six months and one maturing in twenty six years

Each agency assigns their same respective credit rating to a senior unsecured Walgreens Boots bond maturing in six months and one maturing in twenty six years

Corporate bonds only have two risks: credit and interest rate risk. Interest rate risk is unrelated to credit risk. Do you believe the likelihood of being repaid after six months and twenty six years is the same? If not, here’s how the Survival Probability can consolidate both spread and maturity into a single credit risk factor that you can use to compare all corporate bonds:

The impact on Survival Probability of a spread increase and maturity extension for the two WBA bonds with identical agency ratings

The impact on Survival Probability of a spread increase and maturity extension for the two WBA bonds with identical agency ratings

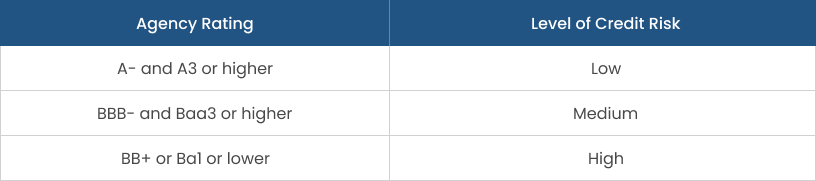

The most useful interpretation of agency ratings is to divide them into the categories of low, medium and high risk for reference as one guideline when considering an investment:

Rating agency levels and their credit risk

Rating agency levels and their credit risk